Menu

- Strona główna

- Zespół Centrum

- Badania

- Publikacje

- Linki

- Kontakt

- Archiwum

- Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

pismo naukowe Centrum - Dalej jest noc - »Nieudana KOREKTA OBRAZU«

- Wybór źródeł

- EHRI PL

Aktualności

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Centrum -Karolina Panz, Zakopiańscy górale a Żydzi przed wojną, w czasie Zagłady i okresie tużpowojennym

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Karolina Panz Zakopiańscy górale a Żydzi przed wojną, w czasie Zagłady i okresie tużpowojennym Spotkanie odbędzie się w środę 18 lutego br. w sali 161 w Pałacu Staszica (ul. Nowy Świat 72) o godz. 11.00 Możliw...

Call for Articles - Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały 2027

Call for Articles 2027 Call for Articles Szacunki i liczby w badaniach nad Zagładą: ograniczenia, zagrożenia i perspektywy W debatach o przebiegu Zagłady często pojawia się element sporu o szacunki i liczby w odniesieniu na przykład do ofiar obozów koncentracyj...

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Centrum: Sylweriusz B. Królak, Zmysłowe kontrasty getta warszawskiego – ucieleśnione doświadczenie przestrzeni Zagłady

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Sylweriusz B. Królak Zmysłowe kontrasty getta warszawskiego – ucieleśnione doświadczenie przestrzeni Zagłady Spotkanie odbędzie się w środę 21 stycznia br. w sali 161 w Pałacu Staszica (ul. Nowy Świat 72) o godz. 1...

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Centrum: Karolina Koprowska, Rozczarowanie i nadzieja – dwa dyskursy o przyszłości Żydów w powojennej Polsce

Otwarte Seminarium Naukowe Karolina Koprowska "Rozczarowanie i nadzieja – dwa dyskursy o przyszłości Żydów w powojennej Polsce" Spotkanie odbędzie się w środę 10 grudnia br. w sali 161 w Pałacu Staszica (ul. Nowy Świat 72) o godz. 11.00...

Premiera książki Karolin Panz pt. Chciałabym opowiedzieć jak zginęło miasto

10 grudnia o godz. 18.00 zapraszamy do Muzeum POLIN na premierę książki Karoliny Panz pt. "Chciałabym opowiedzieć jak zginęło miasto. Zagłada żydowskich mieszkańców Nowego Targu". Z autorką rozmawiać będzie Anna Bikont Postanowiłam, że odtworzę i opiszę h...

NEWSLETTER

Chciałabym opowiedzieć jak zginęło miasto ...

Chciałabym opowiedzieć jak zginęło miasto ...

Zagłada Żydowskich mieszkańców Nowego Targu

Karolina Panz

Warszawa 2025

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 18, R. 2022

Warszawa 2022

PAMIĘTNIK

PAMIĘTNIK

Kalman Rotgeber

oprac. Aleksandra Bańkowska, wstęp Jacek Leociak

Warszawa 2021

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 17, R. 2021

Warszawa 2021

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w latach 1943-1944

Moszek Baum, oprac. Barbara Engelking, tłum. z jidysz Monika Polit

Warszawa 2020

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 16, R. 2020

Warszawa 2020

.jpg) Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Zapiski z okupacyjnej Warszawy

Sewek Okonowski, oprac. Marta Janczewska

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

GETTOWEJ INSTYTUCJI ...

'z Dziennika' i inne pisma z łódzkiego getta

Józef Zelkowicz, tłum. z jidysz, oprac. i wstęp. Monika Polit

Warszawa 2019

CZYTAJĄC GAZETĘ NIEMIECKĄ ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w Warszawie w latach 1943-1944

Jakub Hochberg, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2019

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 15, R. 2019

Warszawa 2019

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 14, R. 2018

Warszawa 2018

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

red. i wstęp Barbara Engelking, Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2018

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

Wspomnienia z warszawskiego getta

Stanisław Adler, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2018

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 13, R. 2017

Warszawa 2017

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

Dziennik pisany w bunkrze (Żółkiew 1942-1944)

Clara Kramer, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Anna Wylegała

Warszawa 2017

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

Zapiski z getta i okupowanej Warszawy

Tadeusz Obremski, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2017

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

Pisma Kopla i Mirki Piżyców o życiu w getcie i okupowanej Warszawie

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking i Havi Dreifuss

Warszawa 2017

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 12, R. 2016

Warszawa 2016

.jpg) SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

Okupacyjne dzienniki Żydów z okolic Mińska Mazowieckiego

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2016

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 11, R. 2015

Warszawa 2015

Mietek Pachter

Mietek Pachter

UMIERAĆ TEŻ TRZEBA UMIEĆ ...

oprac. B. Engelking

Warszawa 2015

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 10, t. I-II, R. 2014

Warszawa 2015

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

Wspomnienia chłopca z Sokołowa Podlaskiego

tłum. Elżbieta Olender-Dmowska

red .B. Engelking i J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2014

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

vol. 9 R. 2013

Pismo Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN

Warszawa 2013

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

Korespondencja wojenna rodziny Finkelsztejnów, 1939-1941

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Ewa Koźmińska-Frejlak

Warszawa 2012

Raul Hilberg

PAMIĘĆ I POLITYKA. Droga historyka Zagłady

tłum. Jerzy Giebułtowski

Warszawa 2012

Monika Polit

Monika Polit

"Moja żydowska dusza nie obawia się dnia sądu."

Mordechaj Chaim Rumkowski. Prawda i zmyślenie

Warszawa 2012

.jpg) Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Bohaterowie, hochsztaplerzy, opisywacze. Wokół Żydowskiego Związku Wojskowego

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2011, nr. 7; Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Jan Grabowski

Jan Grabowski

JUDENJAGD. Polowanie na Żydów 1942.1945.

Studium dziejów pewnego powiatu

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Wspomnienia policjanta z warszawskiego getta

oprac. i wstęp Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2010

Holocaust Studies and Materials

Journal of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research

Warssaw 2010

.jpg) Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

"Przestępczość" Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1942

B. Engelking, J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2010

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2010, nr. 6; Warszawa 2010

Wybór źródeł do nauczania o zagładzie Żydów

Ćwiczenia ze źródłami

red. A. Skibińska, R. Szuchta

Warszawa 2010

.jpg) W Imię Boże!

W Imię Boże!

Cecylia Gruft

oprac. i wstęp Łukasz Biedka

Warszawa 2009

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2009, nr. 5; Warszawa 2009

.jpg) Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Barbara Engelking i Dariusz Libionka

Warszawa 2009

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Perec Opoczyński

Warszawa 2009

Notatnik

Notatnik

Szmul Rozensztajn

Warszawa 2008

.jpg) Holocaust

Holocaust

Studies and Materials.

English edition

2008, vol. 1; Warsaw 2008

.jpg) Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Przewodnik archiwalno-bibliograficzny

Alina Skibińska, wsp. Marta Janczewska, Dariusz Libionka, Witold Mędykowski, Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk, Jakub Petelewicz, Monika Polit

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2007, nr. 3; Warszawa 2007

Prowincja noc.

Życie i zagłada Żydów w dystrykcie warszawskim

Warszawa 2007

.jpg) Utajone miasto.

Utajone miasto.

Żydzi po 'aryjskiej' stronie Warszawy [1941-1944]

Gunnar S Paulsson

Kraków 2007

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Zagłada Żydów, 1933-1944

Raul Hilberg

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2006, nr. 2; Warszawa 2006

"Jestem Żydem, chcę wejść!".

Hotel Polski w Warszawie, 1943.

Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2006

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2005, nr. 1; Warszawa 2005

.jpg) 'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

Szantażowanie Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1943.

Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2004

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

Donosy do władz niemieckich w Warszawie i okolichach, 1940-1941

Barbara Engelking, Warszawa 2003

aaa

ul. Nowy Świat 72, 00-330 Warszawa;

Palac Staszica pok. 120

e-mail: centrum@holocaustresearch.pl

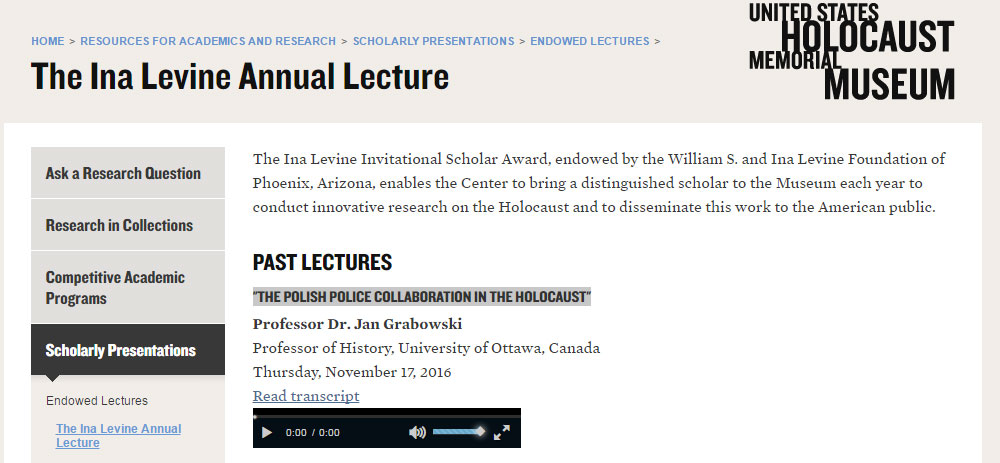

Wykład Jana Grabowskiego w United States Holocaust Memorial Museum o policji granatowej

Wykład Jana Grabowskiego w United States Holocaust Memorial Museum o policji granatowej

09.12.2016 11:00:24

Prof. Jan Grabowski w listopadzie br. w ramach The Ina Levine Annual Lecture w United States Holocaust Memorial Museum w Waszyngtonie wygłosił wykład zatytułowany "THE POLISH POLICE COLLABORATION IN THE HOLOCAUST"

THE POLISH POLICE COLLABORATION IN THE HOLOCAUST

Professor Dr. Jan Grabowski

Thursday, November 17, 2016

In normal circumstances, experts in the history of the Holocaust can be found in the universities, in the museums, sometimes in other research and educational institutions. In my native Poland, however, experts on the Holocaust seem to gravitate to various ministries with particular concentration in the ministry of Foreign Affairs. Each month brings new proofs of the historical excellence of Polish diplomats who dispense knowledge with authority and wisdom. Knowledge, which, for a variety of reasons, eluded professors of history who, quite mistakenly (and naively), assumed that decades of work in the archives, years of gathering of the historical evidence, entitle them to certain insights into the past. Fortunately, the Polish diplomats are ready to disabuse them of this pernicious notion and - with great patience- explain what has really happened in Poland, between 1939 and 1945.

And what has really happened in Poland under the German occupation - according to the Polish diplomats - was an extraordinary eruption of Polish-Jewish friendship and social solidarity as represented by Irena Sendler who - as some venture - saved 2500 Jewish children, by Jan Karski who, in vain tried to alert the indifferent West to the ongoing genocide, or by the elevated number of Poles decorated by Yad Vashem with the medal of Righteous Among the Nations. Therefore, argue the Polish diplomats, all accusations of antisemitism, and of wartime anti-Jewish violence and atrocities perpetrated by the Poles, levelled today at the Polish society are unfounded and unjustified - for all the above mentioned reasons. And should a historian continue to malign and slander the “good name of the Polish nation” suggesting (through malice or ignorance), that certain segments of the Polish society were, in fact, involved in the genocidal German plan to exterminate the Jews; well then such an individual will be placed where he rightfully belongs - in prison. More specifically, for up to three years in prison, according to the new “history” law recently adopted by the government and currently making its way through the parliament in Warsaw.

To help us all to avoid these potentially costly mistakes, the Polish ministry of Foreign Affairs established - and I am not being facetious - a long list of “wrong memory codes”, or expressions which “falsify the role of Poland during WW II” and which need to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly - and not by chance - the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry, includes mostly the expressions linked, one way or the other to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes” which have to be expunged from historical narrative one finds, among others: “Polish genocide”; “Polish war crimes”; “Polish mass murders”, “Polish internment camps”, “Polish work camps (!)” and - most importantly - “Polish participation in the Holocaust”. The theme of the “wrong memory codes” will return today on several occasions.

I would like to dedicate this lecture to Jan Tomasz Gross, Professor of History at Princeton University, who currently faces criminal charges in Poland for having spoken truth about the Holocaust.

WRONG MEMORY CODE? THE POLISH “BLUE” POLICE: COLLABORATION IN THE HOLOCAUST.

The Origins of the Polish “Blue” Police—or the Polnische Polizei des Generalgouvernements

In September 1939 - after four weeks of valiant but hopeless struggle against the vastly superior German forces the Polish state collapsed. The Germans immediately abolished or suspended most of its administrative powers. With time, however, and in the light of the worsening security situation, some institutions had to be revived by the occupant. One of them was the police. On October 30, 1939, Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, the Higher Leader of SS and Police for the Generalgouvernement (as occupied Poland was called), issued an order for all former Polish policemen to report, under the threat of penalties, back to work. The Polish Police (PP) has thus been restored, but in a much-transformed shape. The police corps has been purged of “politically and racially unreliable” elements and all higher officers were fired, or demoted, and replaced with German policemen. During the first months of occupation the ranks of PP, known soon as the Polish “Blue” Police, grew quickly, reaching 10.000 officers and men in the beginning of 1940 and at its peak, in late 1943 - more than 20.000 officers. The Polish resistance, or the so-called Polish underground state, gave the Polish policemen a reluctant blessing to enter the new formation, urging them, at the same time, to do their best to protect the interests of the Polish nation. The “blue” police has thus become the only militarized and armed Polish formation which the Germans allowed to continue in occupied Poland.

FIRST PERIOD - THE “EARLY OCCUPATION”, SEPTEMBER 1939- DECEMBER 1941

The anti-Jewish measures introduced by the Germans struck the Jewish population early, and they struck hard. The limitations placed on the liberty of movement (curfews; bans on public transportation, forced relocations) combined with forced labor, bans on employment and severe financial and property-related restrictions, created hardships which have undermined - already in the fall of 1939 - the foundations of the Jewish community. Historians have focused extensively on larger ghettos, paying special attention to Warsaw, Łódź or Kraków. Much less has been written about the smaller ghettos, although that is where majority of Poland’s Jews lived, suffered and died. It was also in these small ghettos that the German presence was much less conspicuous (often the Germans were altogether absent) and the role of the Polish police grew accordingly. As was the case, for instance, in Opoczno.

Opoczno is a small town situated forty miles east of Radom, in central Poland. In 1939, the city had a population of 7000 inhabitants, half Poles and half Jews. On October 8, 1939, in the nearby Piotrków Trybunalski (soon germanised to Petrikau) after barely a few weeks of occupation, the Germans created a ghetto - the first ghetto in occupied Europe. Opoczno was soon to follow - a ghetto has been created there in the winter of 1940. In practical terms, it meant that one section of the town had to be transformed into a “Jewish quarter”, with Jews being resettled into a small and desperately overcrowded area. This forcible relocation has been done under the tight supervision of the Polish police. It was an open ghetto, with a flimsy and incomplete fence being the only physical barrier separating the Jews from the “Aryan” side. Nevertheless, the borders of the ghetto - although invisible - were very real. A historian might wonder how, in the absence of the German police forces, was it possible to maintain the “invisible wall” of the ghetto? How were the ghetto rules enforced and reinforced by the occupier? What was it that prevented the Jews - at least those, who could and wanted - from fleeing their prison and blending with the Poles outside? The “police station register” - or a detailed record of daily activities of the Opoczno “Blue” policemen offers partial answers to these questions.

Before the end of 1940 the small section of Opoczno designated by the Germans as a ghetto became a deadly trap and a prison for more than 4200 Jews (locals and those resettled from the neighboring communities). The Polish police - in addition to regulating traffic and upholding public safety - enforced the “branding” regulation, which - starting December 1, 1939 - required the Jews to wear white armbands with blue star of David. In the Opoczno police station register we find evidence of arrests of and fines imposed on the Jews found in violation of the branding regulation and for leaving the ghetto and crossing to the Aryan side. It also happened that the Opoczno Jews were harassed by the Polish police for wearing “dirty armbands” - whatever it meant. The police was also instrumental in starving the ghetto, restricting the movements of Jewish traders who tried to bring foodstuffs into the city from the villages nearby. One can assume that the Jewish peddlers and traders arrested and fined by the Polish officers were the unlucky ones who could not afford the bribes extorted as a matter of fact, on daily basis, by the police.

In the fall of 1941 the “Register” started to make frequent references to Polish officers’ cooperation with, or rather their supervision of, the Jewish Order Police. Not much is known about the Jewish police from Opoczno, but it seems that the Polish supervision involved, on the one hand, keeping the Jewish policemen in line and, on the other, conducting joint patrols in the “Jewish quarter”. Joint patrols provided opportunity to perform even more house searches and, inevitably, led to further extortions and seizures of merchandise and goods deemed illegal by the Polish officers. The enforcement of the curfew - in 1941 it was set at 9 pm - was also the task given to the “Blue” police. The Polish officers were also busy escorting work columns of Jews to the sites of forced labor, and making certain that all the designated slave laborers reported for work. In case of truancy it was up to them to find and to punish the offending Jews. All of these activities of the “Blue” police, - however damaging they might be to the Jews of Poland - were but an introduction to the much greater, existential, threats, which were soon to follow.

SECOND PERIOD: DECEMBER 1941–SUMMER 1942

The opening of the next stage of “Blue” police’s involvement in the German policies of extermination can be directly linked to the proclamation of the “III Regulation concerning the Limitations of the Right of Residence in the Generalgouvernement”, on October 15, 1941. The most important part of this legislation imposed death penalty on Jews apprehended outside the ghetto without authorization. Until now the Jews caught on the ”Aryan side” were arrested and sent to prison. Now, it was their life which was at stake. The same penalty was imposed on all those aiding and abetting the Jews on the run - and an important role in the enforcement and in the execution of the new law has been given to the Polish police. If anyone had any doubts as to the true German designs, they were put to rest in the first days of November 1941, when the German Order Police in Warsaw started to transfer the Jews apprehended outside the ghetto into the custody of the Polish “Blue” Police. The case-files were sent to the German Special Court (Sondergericht), while the Jews were incarcerated in the “Gęsia” prison - located in the ghetto and guarded by the Jewish Police. At the same time the Polish Police received instructions to shoot women and children caught trying to cross from the ghetto to the Aryan side (similar regulations regarding Jewish men have been issued several days before). Finally, on November 17, 1941 and on December 15, 1941 the Polish “Blue” Police conducted two mass executions in the yard of the Gęsia prison.

The shootings of the Jews - on German orders - became, in the late fall and early winter of 1941, one of the many additional responsibilities of the Polish “Blue” police. In the period immediately preceding the liquidation of the ghettos, or the implementation of the Final Solution, the policemen in blue conducted executions of Jews in Warsaw, in Ostrów Mazowiecka in Wysokie Mazowieckie , in Tarnów, in Sokoły, in Kraków and in many other locations which are too numerous to be listed here.

The killings of innocent people were a logical progression in the ever-increasing wave of terror directed at the Jews. The “humble” beginnings of 1940 and 1941 were a springboard, with a steep learning curve, to the killings of 1942. The robbery, the exploitation, the assaults, the beatings and the humiliation of the pervious period paved way to the next stage and made the Polish policemen an important, often indispensable, element in the German machine of extermination.

THIRD PERIOD: EINSATZBEREIT. THE LIQUIDATION ACTIONS, 1942.

In 1942 constable Lucjan Matusiak was promoted to deputy-chief of the Polish “Blue” police station in Łochów, a quaint town fifty miles north-east of Warsaw. More importantly, it was in the summer of that year that Matusiak graduated from simple cop to a murderer. Matusiak’s education was linked to the liquidation of the Łochów-Baczki ghetto, a relatively small ghetto with no more than one thousand Jewish inmates. During the liquidation, the Polish policemen, Matusiak among them, operated alongside their German comrades and masters, the gendarmes. One has to say that Lucjan Matusiak and his fellow officers did not become killers overnight. They observed the Germans at work and - with time - became skilled apprentices.

According to the Polish witnesses, the Polish officers, together with the gendarmes, moved from one Jewish house to another, pulling the hidden Jews out of their hideouts in the walls and in the attics. One of the Poles stated after the war: “I saw with my own eyes Lucjan Matusiak and the gendarmes hunting down the Jews. I saw him leading three Jews: Czerwony, Złotkowski and another one whose name escapes me, all of them were from our village. Matusiak, who led the Jews, knocked on the doors and ordered them to take shovels and to follow him. Later he told us [Poles- JG] to go into the ex-Jewish [pożydowski] houses and to throw the beds, bed covers, furniture out, into the street. In the meantime, the gendarmes stood over the Jews who dug a grave for themselves. And then Fredek, the chief gendarme, shot these Jews”.

A few days later, during the final liquidation of Baczki, Matusiak and other Polish officers started to kill the Jews on their own. These were awkward, initial steps, with the Polish policemen firing randomly and inaccurately, and the Germans having to finish off the wounded Jews themselves. Nevertheless, the evolution from murderers’ apprentices to murderers in their own right was, in the case of the Polish policemen, rather swift. One can even venture that the policemen proved to be very diligent pupils who, in many cases, even before the end of 1942, surpassed their teachers, the German gendarmes. We will revisit platoon leader Lucjan Matusiak again in a little while.

While policeman Matusiak was honing his new skills in Łochów, his colleagues in Opoczno were loading the Jews into cattle wagons destined for Treblinka. And after the train has left the station - as the Opoczno station register informs us - they went to the empty ghetto to prevent the local “Aryan” population from looting the “abandoned Jewish property” - to quote the language of the documents. While the Jews of Opoczno were on their way, on their last way, the Jews of Węgrów (town located one hundred and forty miles to the northeast of Opoczno) were preparing for the celebration of Yom Kippur. They did not know that the same day the local “Blue” Police had been put on alert.

Early in the morning, on September 22, 1942, the cordon of German and Polish policemen and their Ukrainian helpers was rapidly closing around the city. Between 4 and 5 am, the ring finally closed. Węgrów was now cordoned-off in such a way that the policemen taking part in the “Action” were spread apart at intervals of no more than 100 meters. On September 22 the sun rises at 6:15 am, but the sky starts to brighten around 5:00 am so that the members of the Liquidierungkommando could see each other. The “Blue” police have been directly involved in the Aktion from the first moment, entering the city with the German forces, conducting house searches and herding the Jews towards the town square - the central assembly place. Early in the afternoon, shortly after 2 pm, the majority of Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto have already been rounded up and delivered to the market square. While the roving squads of Germans, Ukrainians and Poles searched the houses for bunkers and hideouts, some of the members of the Liquidierungskommando began mass executions of the elderly in the Jewish cemetery.

The mayor of Wegrow noted in his memoir: “the removal of the bodies had already started. There were carriages and people were ready - they volunteered for the job without any pressure. Our hyenas were after Jewish clothes, footwear and the cash which could have been found on the dead”. While some were robbing the bodies left behind in the ghetto, others were busy at the site of the execution, in the cemetery: “My friends, who found themselves at the cemetery, had tears in their eyes when they told me about the wounded being buried alive together with the dead, and with the grave diggers finishing-off some of the Jews with spades and stones”. Some citizens of Węgrów took off with more than clothes and shoes of the dead: “they even pulled out golden teeth with plyers. That’s why people in Węgrów called them “dentists”. The “dentists” sold their merchandise through fences and go-betweens. When I mentioned to one of them (he was a court clerk) that this gold was soaked in human blood, he told me: ‘impossible, I personally washed off this stuff” - wrote mayor Okulus

The “hyenas” took their clues most of all from the Polish “blue” police and from the members of the firefighting brigades. The firefighters, led by Ajchel, their chief, showed up in the liquidated ghetto: “and they threw themselves [on the Jews - JG] like hunting dogs on their prey. Henceforth, they “worked” hand in hand with the Germans and - as locals and firefighters - did it much better than the Germans” noted the previously quoted Okulus. Chief Ajchel carried around a briefcase into which his men deposited precious objects taken from the Jews. Their plan was to pool their resources and to split the loot in the evening, after “work”. Müller, the chief of Węgrów Schupo, recognized the contribution made by the Polish police and firefighters, and met with some of them in the evening in a local restaurant: “He pulled out from his case a wad of money, and gave it to them saying ‘here, this is for your good work”.

There were hundreds of ghettos in Poland (in Nazi-occupied Poland, of course) and their liquidations followed a very similar, and equally horrible pattern where the “Blue” police, the firefighters, the “bystanders” and even the children had a role to play and choices to make. Węgrów was no exception. The ghetto in Biłgoraj, fifty miles south of Lublin, was being liquidated on November 2, 1942, ten days after Węgrów. Jan Mikulski, a Polish forester, on that very day was on his way to the bank to pick up some cash for his workers (life had to go on, after all) when he saw: “many bodies of women and children laying in the streets, in the gardens and on the squares. Wiesiołowski, the commander of the Polish police, surrounded by scores of kids aged 6-12 searched the attics, cellars and sheds. For each Jewish child brought to him he gave the [Polish - JG] kids sweets. He grabbed the small Jewish children by the neck and shot them with his small-caliber revolver through the head”

It is not the horrible and gory details of executions which are the most striking part of these descriptions. Writing about the Holocaust touches, after all, upon darkest aspects of human nature and upon the most evil human actions. What is striking here is the wide geographical distribution of the discussed historical evidence: segments of the local population seem to have taken an active part in the genocidal German project all across the occupied land.

SECTION 1: THE PAINFUL ISSUE OF BULLETS

On the day of the Aktion in Węgrów more than one thousand Jews have been murdered in the streets of the city by the German-Ukrainian Liquidierungskommando, with the help of the Polish police, the local firefighters and with the assistance of the so-called bystanders. Another 8000 Jews were marched to the Sokołów railway station, eight miles distant, and delivered to Treblinka. The German-Ukrainian Liquidation kommando left Węgrów the next day. Their job, however, was far from over. More than a thousand Jews remained still hidden inside the ghetto. Over the next days and weeks, the Polish “Blue” police and the local firefighters conducted intense searches, found most of them and either killed them themselves, or delivered them to the German gendarmes for execution.

While Jewish Węgrów ceased to exist, the Jews of Wodzisław, a small town half-way between Kielce and Kraków, were still hoping against hope. Their ghetto, created in 1940, had a population of close to 4000 people. Like in so many other small ghettos there were no walls or fences to separate the Jews from their “Aryan” neighbors. Likewise, there were no Germans to speak of in Wodzisław and the forces of order were represented by the local “Blue” policemen. The Wodzisław unit reported to the county police headquarters located in nearby Jędrzejów. Some reports dealt with staffing issues, with overtime, with learning of the German language by the officers, and with minor matters of discipline. Other reports dealt with ammunition: the German ORPO officers attached to the Polish “Blue” police were, as we can see form the exchanged correspondence, notoriously stingy with live ammunition. The Germans feared, for a good reason, that the “Blues” would either sell the bullets on black market or even use them against the occupation authorities. In 1942 there was not much in terms of organized resistance against the German rule but by 1943 and 1944 the loss or theft of bullets could bring a Polish policeman in front of the SS and Police Court in Kraków [SS und Polizei Gericht Nr 6 (Krakau)] and consequences could be dire. It is not surprising, therefore, that - before issuing further supplies - the Germans expected a thorough and very detailed account of all expended ammunition. Until mid-1942 the requests for new ammunition filed with the Germans most often gave stray or rabid dogs, as a reason for the shootings.

In the summer and fall of 1942, however, the realities of Endlösung overtook and transformed the police routine relegating the shootings of stray dogs to a distant, second place. Henceforth it was the Jews whom the “Blue” policemen would target most frequently. And so, in November 1942, in anticipation of the upcoming liquidation of the Wodzisław ghetto, the Germans provided the Polish officers with a fresh supply of ammunition. The bullets came handy, because the local policemen seem to have fired often and fired well. In the Encyclopaedia of ghettos and camps, published by the USHMM, there is an entry devoted to Wodzisław in which some attention has been given to the liquidation of the Jewish quarter: “The town had a small Polish (Blue) Police force, consisting at first of three and then two policemen, named Szczukocki and Machowski.”. “The Germans liquidated the Wodzisław ghetto on or around September 20, 1942. Following the liquidation Aktion, the German authorities established a remnant ghetto in Wodzisław. At the beginning of November 1942, 90 Jews lived there, but this number reportedly grew to 300 before its liquidation that same month. On November 20, the remaining Jews were resettled to the Sandomierz ghetto”.

The USHMM encyclopaedia gets it mostly right but the records of the Polish “Blue” police allow us to make some important corrections to the existing narrative. In a report dated November 21, 1942, one day after the final liquidation, the commander of the Wodzisław police station listed the number of expended bullets per each officer.

The “Blue” policemen, if we are to trust their reports, have fired on that fateful day 300 bullets. First, not one officer - as we read in the encyclopaedia - but all of them were involved in mass-murder of the Jews of Wodzisław. On average, the Polish policemen fired at the Jews between 15-20 bullets each but platoon leader Józef Machowski applied himself more than his fellow officers and during the Action expended 36 bullets. The report reads: “I request a replenishment of carabine ammunition for the local detachment of the Polish Police. The bullets have been fired against the Jews by the officers of this police station during the most recent deportation of the Jews from Wodzisław. Names follow”. The police reports - and three such reports have been preserved from the period during which the Wodzisław ghetto has been liquidated - testify to the fact that not only all Polish officers took part in the Einsatz but that sergeant Władysław Buczek, their commander and the author of the reports, requested for himself 20 additional bullets - in exchange for those fired at the Jews. According to the Jewish survivors of the Aktion in Wodzisław, close to 200 Jews have been killed in the streets of the ghetto at that time.

We can now make further corrections to the above quoted encyclopaedia entry. First, there were not three, but twenty Polish officers in Wodzisław on the day of the final liquidation. Second, it is highly unlikely that on November 20th, 1942, three hundred Jews were marched to Sandomierz; instead they were killed by the Poles in Wodzisław. If any Jews at all have been resettled to Sandomierz, it must have been those who avoided the mass execution. The police documents quoted above force us - even at the risk of triggering the “wrong memory codes”- to acknowledge the role of the previously unreported murderers - the Polish “Blue” policemen.

Keeping in mind the requests for bullets made by the policemen from Wodzisław, and knowing about the tight control over ammunition exercised by the German Order Police (ORPO) we can once again take a look at platoon leader Lucjan Matusiak, the previously mentioned apprentice-killer of the Jews from the Łochów detachment of the “Blue” police. This time however, our travel through the Holocaust will take us to June 1943, eight months after the liquidation of the last ghettos in the area and during the period of so-called hunt for the Jews, a pursuit which the Germans called das Judenjagd.

FOURTH PERIOD: 1942-1945, THE HUNT. ON DUTY IN ŁOCHÓW AND GRĘBKÓW.

In late June 1943, constable Lucjan Matusiak caught himself four Jews: two men, one woman and a child. Actually, he did not catch the Jews himself; they have been delivered to him, hands tied behind their backs with wire, by the local peasants. The event was rather unremarkable - after all, by mid-1943, Matusiak and his fellow officers have been hunting down, robbing and murdering the Jews on regular basis for nearly a year. It can even be said that, between 1942 and 1943, the officers in blue acquired extraordinary expertise in this particular area of police work. Their victims were either local Jews who went into hiding - Łochów, until 1942, had a sizeable Jewish population - or Jews who escaped from the death trains. The railway line Warsaw-Tłuszcz-Małkinia, which passes through Łochów, became - between July 23, 1942 and late summer 1943 - the main transportation route delivering victims to the gas chambers in the not-so-distant Treblinka extermination camp. As we know well from the testimonies of rare survivors - the testimonies being corroborated by hundreds of graves lining the railway tracks - the Jews tried to flee the deportation trains. They pried open the wooden planks of the wagons, they tore away at the barbed wire which covered the small openings in the cattle-cars, and fled. Many were wounded, or killed during the dangerous jump, or were shot by the soldiers guarding the death transports. Some, however, managed to make it into the heavily forested areas close to the railway tracks and, later, looking for help, reached the local hamlets and villages. That’s where some of them encountered Lucjan Matusiak and his fellow officers in dark-blue uniforms of the Polish police.

We do not know whether the four Jews who found themselves at the mercy of the Polish constable in June of 1943 were local Jews hiding in the area, or people who fled the death trains. Whether they were local Jews, or Jews from Warsaw is, however, of little importance. What was important was their number - number which made constable Matusiak face some hard choices. He had to kill four Jews, and he had only one or two bullets left. Wacław Chomontowski, an eyewitness and one of the local “bystanders”, described the whole situation in following words: “I have seen with my own eyes how officer Matusiak executed 4 Jews using one bullet in the village of Łopianka. He stood these four Jewboys in a row, one behind another, and shot the last one in the back. There was also a young Jewish lad (żydziak), so he killed him with a separate bullet. Once he had shot the Jews, he told me and the others to dig a grave, but told us to make it shallow, not to dig too deep. When we laid them into this ditch one Jew, who had only been wounded, started begging: “mr. officer please, have mercy, finish me off!”, to which constable Matusiak responded: “you are not worth a bullet, you will croak anyhow!”. Another “bystander” - a term which the historians of the Holocaust in the East are more and more reluctant to use - described the same event in a slightly different manner, in more detail: “he [Matusiak - JG] lined up the Jews one next to the other and at the end of the row he placed this boy, who was perhaps thirteen - and then he shot them with one bullet. The boy was killed right away, but the older Jews were badly wounded, and one Jewboy [żydek - JG] begged: “officer, please, finish me off!”. But officer Matusiak said that he had no more bullets left. Then he told us to bury them and then he stomped on the dirt with his feet, not listening to the pleas of the wounded Jew”. “So we buried them, but, when I came back a while later ” - continued his deposition witness Chomontowski - “I could see the earth moving and I could hear the wounded Jew still moaning beneath”. Chomontowski did not elaborate why he had not thought - at that late stage - of saving the wounded Jew buried alive under his feet. This might be the first of the many troubling questions which come to mind reading the records of the court proceedings from the period immediately after the war: did Chomontowski fear the return of “blue” policeman Matusiak? Or did he, like so many others across the occupied land, simply assume that for the Jews death, one way or another, was inevitable? That digging the wounded man out of his grave would be pointless?

There are several other troubling questions related to the execution in Łopianka. Some of them will, no doubt, trigger the “wrong memory codes”, which still today, more than seventy years after the fact, preoccupy authorities in Poland. First, the killings of Jews in Łopianka occurred in the absence of any Germans and without any German knowledge or direct involvement. Indeed, constable Matusiak acted out of his own initiative; he solved the Jewish question as well, as he could. Because there was little doubt in his mind that the Jewish question had - one way or another - to be solved. Furthermore, the “Blue” policeman was not acting alone; he could rely on at least some of the local inhabitants to assist him in his work. Third, constable Matusiak was not, from what we know, a vicious killer, who had been hired by the Germans for his murderous skills, to do their bidding. In fact, he was just a regular small-town cop, with eleven years of pre-war experience in the Polish police. From what we can see in his file, he was an ordinary man, whom circumstances, antisemitism, greed, fear and opportunity transformed into a killer. And finally, we have the question of bullets. No doubt, by mid-1943 officer Matusiak was a vicious killer and a sadist. But he also had a rational explanation for his sadism: the German reluctance to share ammunition with their Polish underlings.

PATRIOTIC POLICEMAN KRÓLIK

Grębków is a small village, fifty miles east of Warsaw, just north of the Warsaw-Siedlce highway, few miles past Mińsk Mazowiecki and not so far from Dobre [the place of hiding of Henryk Grynberg who is here today with us]. The scenery is beautiful, idyllic, with rolling hills, fields, lush meadows and charming woods. Before the war in this area Jews made up more than a half of the local townspeople but they were also fairly numerous in smaller villages. In the spring of 1942 the 142 Jews of Grębków have been seized by the local “Blue” policemen, placed on carts and delivered to the nearby ghetto in Węgrów, from where they were taken to the extermination camp in Treblinka. Those who stayed behind, went into hiding. Unfortunately for them, Grębków was home to a detachment of the Polish “Blue” police under the able command of sergeant Bielecki and his deputy, platoon leader Królik. Sometime in November 1943 (it is difficult to pinpoint the exact date, witnesses giving conflicting evidence), sergeant Bielecki received a confidential report from one of his many trusted sources, about Jews hiding in the area. The “confidential source” got it right: a short search of the house of Aleksandra Janusz in village Gałki, few miles away, revealed the presence of nine Jews hidden in a primitive hideout, sort of a crypt, dug out under the dirt floor of one of the rooms. Mrs. Janusz, the badly frightened rescuer, recalled that, as soon as they showed at her door, officers Iwanek and Królik started shouting: “hey, where are the poodles!?”. Ms. Janusz, pretended not to know who were the wanted “poodles”, but the policemen kept saying one to another, visibly amused: “oh yes, yes, she has the poodles!”.

The levity of both policemen is lost in translation - “Królik” in Polish means “rabbit”. The notion of a rabbit chasing the poodles might have seemed hilarious to the arresting officers. Once the jokes were over, however, officer Królik took a pitchfork and - visibly very well -informed about the location of the hideout - went looking for the trapdoor leading to the cellar. The door had been covered with manure and dirt. And under the manure-covered trapdoor were the Jews, or - as officer Królik jokingly referred to them - the poodles. Grochal descended into the hole and, not without trouble, hauled all of the offending “citizens of Jewish nationality” - to quote the language of the documents - to the surface. The Jews and the cops, as it immediately became obvious, were no strangers. The Rubins, their children, Mrs. Gurszyn and Mrs. Kajzer, all of them hailed from the nearby Kałuszyn. Officer Królik, when he saw the Jews emerging from the pit started to laugh and said: “Ho, ho, Mr. Rubin, I know you! You are from Kałuszyn and you made shoes for me! Don’t worry, we won’t hurt you. We will just lead you toward the forest, we will shoot a few times in the air and you will run for cover! I won’t shoot you!”. After a while, four more officers entered the house of Janusz and, according to the rescuer’s daughter, the still-smiling officer Królik grabbed from Rubin the shoemaker a wad of banknotes. Once Królik took the money off his victims, he and three other policemen marched the Jews towards the woods. Soon after the peasants of Gałki heard numerous shots coming from the distance. In a little while, the “Blue” policemen returned to the village and Krolik asked Mrs.Janusz to bring hot water, because they needed to wash blood off their hands. Once the officers washed their hands, constable Iwanek tried to extort from Mrs. Janusz 3000 zlotys as a fine “for having sheltered the Jews”.

Emanuel Ringelblum, the historian of the Warsaw ghetto, spent last months of his life hiding in a bunker, in Warsaw. In the winter of 1943/44 he wrote his last book which was a somber analysis of the Polish-Jewish relations during the war. It was a bitter text, written by a Polish Jew who saw his entire nation murdered in plain sight. Ringelblum also had a word to say about the murderers in dark-blue uniforms. Referring to the “Blue” policemen, he wrote: “the blood of hundreds of thousands of Polish Jews, caught and driven to the “death vans” will be on their hands”. Referring to the blood on the hands of the Polish policemen Ringelblum was using a figure of speech, a poetic metaphor. But then, Ringelblum has not met constable Królik, the “Blue” policeman from Grębków.

What initial insights can one gather from the fate of the Rubin family from Kałuszyn? First, the frequency, or the near-certitude of betrayal which resulted in “confidential information” being shared with the “Blue” police. Betrayal which - due to the wide-spread antisemitism and hate of the Jews, was combined with the universal conviction about the “Jewish gold” just waiting to be transferred to new owners. The myth of “Jewish gold” was so popular and so deeply-rooted among Christian Poles, that it sealed the fate of Rubin, the poor shoemaker from Kałuszyn. Once again - at the risk of repeating the “wrong memory codes” - one has to stress the prevailing atmosphere of fear and anitisemitism which proved to be devastating to Poles who dared to engage in rescue efforts - and which was much more deadly for their Jewish charges. Third observation concerns the surprisingly large margin of independent action, or own agency of the “Blue” policemen in cases involving the Jews. The constables arrested, robbed and murdered their victims without any German orders and without their knowledge. Last but not least, Polish policemen did not kill strangers; they killed their neighbors whom they had known - as was the case of Mr. Rubin, the shoemaker and his family - from before the war. After the war, responding to charges of murder, the “Blue” policemen often argued that, in fact, killing of the Jews was a patriotic act. An act which saved the Polish villagers from the wrath of the Germans, who would have learned sooner or later about the Jews in hiding and who then would have burned down the entire village, or shot several Polish hostages.

There was, however, more to constable Królik than met the eye. In his personnel file which by chance survived, in the largely depleted collection of the SS and Police Court from Kraków ( SS- und Polizei Gericht ) we can find several laudatory opinions about the constable from Grębków written by his German superiors: “Krolik ist ein tüchtiger, energischer und tapferer Polizeibeamter [Krolik is an efficient, energetic and brave police officer - they wrote]”. Not only the Germans were fond of policeman Królik; his war-time contributions were equally praised by his superiors in the Polish resistance. Królik, as we learn, was also a patriot and a soldier of the II Department [code “Smoła” (“Tar”)] of the Home Army (AK) responsible for gathering intelligence in the Węgrów area. Both Królik and Grochal have been described by a historian of the Węgrów area resistance as men “belonging to the most valuable human element among all the social strata ”. It is not surprising, therefore, that Królik was widely respected by his peers and by his community.

MEANWHILE , IN WARSAW: THE BRAVE ASSOCIATES IN MURDER

The “Blue” police struck the Jews hard and it struck them all across the occupied land. The “exploits” of policemen serving in rural areas differed from the tactics employed by their colleagues serving in large cities, but - at the end of the day - the Jews died either way. If one were to assume - on the basis of the evidence presented earlier - that the Polish “Blue” policemen in rural areas were particularly deadly, one would assume wrong. It is known that one of the duties of “Blue” police in Warsaw was to guard the ghetto from outside as well as from within. After the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto which occurred in the summer of 1942 - the Polish police remained on duty, to control the 50,000 Jews still alive in the remnant ghetto.

On April 19, 1943, the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto had started and at the same time - its brutal suppression. There were 85 German soldiers and policemen either killed or wounded in this “battle with the Jews”. In his Report “The Jewish Quarter in Warsaw Exists No More”, SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop wrote of his dead: “they gave to the Führer and to the Fatherland what they had most precious: their lives. We shall never forget them!”. Constable Julian Zieliński of the XIVth precinct of the Warsaw “Blue” police, who - as we read - “was killed in the fulfilment of his duties by the Jewish bandits” was also among the dead. Several other officers from the1st, 7th and 8th precincts found themselves among the wounded. Let me, once again, quote from gen. Stroop’s report: ”The Polish police, encouraged with additional payments, strives to deliver to the nearest police station every Jew who dares to show up in the city”.

The “Blue” police was not only guarding the burning ghetto from the outside. Many Polish officers found themselves in the very “heat of the action”, to use this military expression. Leon Najberg, one of the survivors of the Warsaw ghetto uprising wrote in his diary : “Wednesday, 26 May 1943. When Fugman saw the pistols in the hands of the Polish policemen, he made his last statement: “You German lackeys! I will be avenged!”. The police scum opened fire. [...] Next to the wall of the house at Swiętojerska 38, in front of the dump, we saw the bodies of women, girls and children. They looked like a heap of rags; useless discarded items. But their twisted arms and legs showed that just a moment ago they were still alive. In the light of pocket lamps, we recognized familiar faces. [...] We talked quietly in Yiddish about this new link in the powerful chain of crimes committed by the Polish-German block. Thursday, 27/V/43. Our co-citizens [the Polish policemen], the brave associates in murder, were not yet done. After yesterday’s killing they returned today - to plunder. Policemen from the 17th and the 18th precincts in Warsaw showed up today, before dawn, around 4 am. , at the courtyard of Wałowa 4 and tore off clothes from the bodies of not-quite cold Jewish victims. There were 25 Polish hyenas armed to the teeth with various firearms and grenades who were involved in this blasphemy”

The victory in the battle against the Jews of Warsaw did not mean, however that the Polish officers, (aptly named by Najberg “brave associates in murder”) could remain on their laurels. In their on-going hunt for the missing Jews they received significant help from their colleagues, members of the pre-war investigative units, now known as the Polish Criminal Police, or the Polnische Kriminalpolizei.

POLISH KRIPO (POLNISCHE KRIMINALPOLIZEI) AT WORK

Historians know practically nothing about the wartime activities of the Polish Criminal Police (PPK, the Polish Kripo) . The handful of studies of German police rarely mention the PPK, and then usually briefly. The role of the criminal police in the extermination of the Polish Jewry remains unknown. In contrast to the more familiar “Blue” police, which the Germans subordinated to their Order Police (Orpo), the Polish Criminal Police became part of the German Criminal Police, Kripo, a section of the Security Police (SIPO). Polish officers of the Kripo came mostly from the Investigative Office, the elite of the pre-war Polish police. In theory, the Polish Criminal police was to focus on fighting common crime. In fact, the Polish Kripo became one of the essential components of the Nazi terror apparatus. As the occupation went on, Jewish survivors fighting to stay alive in Aryan society became a focal area of the Polish Criminal Police work.

Emanuel Ringelblum, historian, social activist and the founder of Oneg Shabbat, the archive of the Warsaw ghetto, was just one among the many Jews who have had the misfortune of coming to the attention of the Polish Kripo. In the fall of 1943 Ringelblum , his wife Yehudis and son Uri, went underground, and hid in a bunker. They survived in their hideout until early March 1944. The bunker - called by its occupants “Krysia” was an extraordinary feat of engineering. Located in southern part of Warsaw, on the outskirts of the city, under the greenhouses of Mieczysław Wolski, a courageous Pole, “Krysia” housed, at times, close to forty Jews. In Warsaw, in 1944, in terms of Jews in hiding, there was nothing which would even come close to the size of “Krysia”. By then, after two years of relentless hunt, the remaining Jews of Warsaw preferred to hide individually, very rarely in small family-size groups. To have a bunker with dozens of people still undetected, in Warsaw, in 1944, was simply unheard of. While in hiding, in the darkness of the bunker, Ringelblum worked on his last manuscript: the history of wartime Polish-Jewish relations. Writing what was to be his last book, Ringelblum had to also reflect on the role of the “Blue” Police: “ The Polish Police, [...] “ – he wrote – “has played a most lamentable role in the extermination of the Jews of Poland. The uniformed police has been an enthusiastic executor of all the German directives regarding the Jews [...] “. Although Ringelblum knew well the threats awaiting the Jews hiding on the “Aryan” side, he could not know about the new tactics of hunt developed by the Polish criminal police.

In the fall of 1943, just about the same time when Ringelblum entered “Krysia”, the Polish Criminal Police created a specialized unit to track and arrest Jews in hiding in a more efficient way. Incidentally, similar specialized units existed in other occupied countries. The Parisian police had a unit known as “mangeurs des Juifs” the Dutch had their own and equally deadly “Hennicke columns” and Belorussians and Ukrainians sent to the field thousands of uniformed and ununiformed killers. The only difference is that while the French and the Dutch policemen and - to a lesser extent their Ukrainian and Belorussian counterparts- have been studied extensively by historians, deadly silence surrounds the exploits of their Polish colleagues. The new section of the PPK was named the Kriegsfahndungkommando, the Commando for Wartime Searches, an euphemism, but according to a testimony, the door to the room out of which the commando agents operated, bore a plaque with the telling sign Oberstreifkommando (Main Office for Manhunts). The Polish employees of the Warsaw Kripo simply called this unit “the Jewish office.” The Commando for Wartime Searches was headed by SS Untersturmführer Werner Balhause. The majority of the Manhunt’s Office employees were Polish detectives, crème de la crème of the Polish investigative units from before the war. The day-to-day work of this office relied on the informer network. Every agent ran his own spy ring. Thus, Sergeant Głowacki ran ten informers and collaborated with an agent for special missions, one Jan Łakiński, who would soon be executed by the underground. Anonymous reports sent to the police in large numbers also played an important role in the work of the unit.

Early March 1944 proved to be very successful for the agents of Polish Criminal police. On March 1st Julian Grobelny, chairman of Żegota - the underground Council of Aid to Jews - was arrested in Mińsk Mazowiecki. One day later Jan Jaworski, “a member of the committee [to aid] the Jews” was arrested in a coffee shop in Mokotowska Street, where he was to meet with Kripo agents to hand over a ransom for releasing Jews who had been arrested earlier. On March 3rd the agents arrested a large group of Jews in hiding in Koźla Street. And four days later, the agents of the Special Unit of the Polish Criminal Police learned about the location of bunker “Krysia”.

Uncovering the bunker in which Emanuel Ringelblum was living was one of the greatest successes of the Kriegsfahndungskommando of the Polish Criminal Police. The operation can be reconstructed with reasonable accuracy thanks to the testimony of two men who took part in it. On Tuesday, March 7, 1944, as soon as the officers arrived at work early in the morning, Untersturmführer Balhause raised the alarm. After a short briefing, the officers got into cars. Detective Glowacki noted: “Balhause ordered us to follow him. We drove to Grójecka Street, I don’t remember the number, it was between Narutowicza Square and the last tram stop in the direction of Okęcie airport. When we arrived, we saw a dozen or so Germans from the Gestapo. We entered the property through a gate, there were greenhouses there, the Gestapo and we surrounded them. I learned that the gardener who owned the greenhouses and his teenage son had been arrested. One of the Germans ordered the gardener’s son to go down into the bunker under the greenhouses and explain to the Jews inside that all resistance would be pointless and that they should all come out. The Jews came out of that bunker one by one; there were more than twenty of them, and they were arrested by the Gestapo. These Jews were of different genders and ages, there were even children. After the arrests, the Jews and the gardener and his son were transported to the Gestapo command, while we returned to the headquarters. Another Polish detective noted that: “These Jews had been hiding in a comfortably furnished greenhouse cellar. They had running water, a bathroom and electricity. Gardener Wolski delivered their food. The Jews had been hiding there since March 5, 1943. The Jews were taken away with their belongings (furs, jewelry, 4 kg of gold, etc.). The greenhouse and all the furnishings were destroyed with hand grenades and burned down”. “From what I can remember, nearly everyone from our section and many agents from the Command and other Police Stations took part in liquidating the bunker filled with Jews in Ochota” – he added. While the Polish Kripo arrested the Jews, all men from the 23rd Warsaw precincts of the Blue Police kept order on Grojecka street where hundreds of bystanders gathered to watch the event.

A week later Emanuel Ringelblum, Yehudith, Uri and the rest of the Jews were murdered in the ruins of the ghetto, most likely at the same spot where the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (called with unintended irony the “Museum of Life”) - stands today. It can be assumed that Wolski the brave rescuer and his nephew died at about the same time. The men from the Manhunt’s Unit of the Polish Criminal Police disappeared without a trace other than the few scattered documents which allow little more than to signal the degree of terror and pain inflicted by them on the dying Polish Jews.

CONCLUSION

The title of this lecture implies collaboration of the Polish police with the Germans. Were they, however, in fact collaborators, or did they pursue their own agenda, one which was not necessarily in line with the wishes of their German masters? From the point of view of the Jewish victims these distinctions mattered little. Actually, they did not matter at all. For a Jew, falling into the hands of the Polish police meant, in practically all known cases, certain death. And death followed the “Blue” policemen everywhere – Wodzisław, Opoczno, Warszawa, Biłgoraj, Węgrów or Łochów were by no means not unique. Neither were the methods used by the Polish police. The historical evidence – hard, irrefutable evidence coming from the Polish, German, and Israeli archives – points to the pattern of their murderous involvement visible throughout Poland. Emanuel Ringelblum, himself a victim of the Polish detectives, suggested that the Polish policemen were responsible for the deaths of “hundreds of thousands of Polish Jews”. We will never, of course, know the precise numbers. Some policemen were killing, others were tracking the Jews down and still other were shutting the doors of cattle wagons headed for Treblinka or Bełżec. But Ringelblum offered us an order of magnitude which should be a challenge to historians. The Jewish victims of the Holocaust, in many cases people who had a fighting chance to survive, deserve nothing less.

Today, in Poland, attempts are being made to portray the “Blue” police as true Polish patriots, deeply engaged in the resistance, unsung heroes of the struggle against the Germans. In very many cases this is true. Unfortunately, as we know, patriotic engagement could go hand-in-hand with the involvement in the German policies of extermination. Not that this particular insight was of any value to the creators of the monument dedicated to the memory of the “Blue” policemen from Kraków, executed by the Germans. The monument, erected in 2012, could have been placed in several different locations: in front of the Kraków police headquarters, for instance. Not so; without being excessively subtle, the monument now sits right in the middle of the site of the former Płaszów concentration camp, place of death of 20,000 Jews of Kraków. Many of whom have been arrested and delivered to Płaszów, to be executed, by the officers of the Polish police. Wrong memory code? Not this time, I fear.

Had policeman Królik, Matusiak and thousands of their fellow officers demonstrated less enthusiasm for tracking down and killing the Jews, had the firefighters from Markowa, from Stoczek, from Węgrów and from hundreds of other locations, shown more interest in putting down the fires and less in killing the Jews, had the “bystanders” chosen to stand by rather than to engage in the search for the desperate victims, many more Polish Jews would have survived the war. In Poland, if we leave out those Jews who have fled to the Soviet Union and who never found themselves under the German rule, the percentage of survivors stands at about 1%. In other words, out of one hundred Jews one lived until 1945. Which did not mean that all of them survived the subsequent pogroms and murders of the post-war period - but that is a different story.

Where does it all leave us? Far from engaging in new interpretations, we are faced with new historical evidence that actually can reshape our understanding of certain aspects of the Holocaust. Far from shifting the blame away from the Germans, the evidence points to the fact of wide-spread acceptance of the German genocidal project. However efficient, the German system of extermination was, at least in part, based on improvisation. Orders coming from the top were lacking precision on purpose, allowing lower ranks to improvise. In many countries the local institutions, and individuals, simple people, became - in a variety of ways - complicit with the Germans. Most were moved by antisemitism, although different other justifications might have been later offered in order to explain the heinous acts. It was their participation which, in a variety of ways, made the German system of murder as efficient as it was. The deadly efficiency accounted not only for the deaths of tens of thousands of Jews who were found in hiding but also for the deaths of those who - having seen the threats on the Aryan side - decided not to hide in the first place.

David Cesarani, in his book “Final Solution”, quoted one of the “bystanders” who claimed that for the Germans the execution of three hundred Jews at Ponary meant the removal of three hundred enemies of humanity. For the Lithuanian auxiliaries involved in the massacre the same three hundred Jews represented, he argued, three hundred pairs of trousers and shoes. In the light of the murderous actions of the Polish “Blue” Police one might want to put Cesarani’s witness claim to question. Was it simple greed which provides the necessary justification and helps to explain the zeal, the application and the frequency of killing sprees committed by local enablers of the Nazis? One can rather doubt it - after all, and despite the widespread violence, it was not all the shoes and not all the trousers which became fair game. Christopher Browning, one of the most insightful historians of die Täter, of the perpetrators, argues that for the Germans, the killing of the Jews was a matter of duty: following the orders and responding to a group pressure of their comrades. In the case of the Polish “Blue” policemen, or the Polish firefighters (or Lithuanian auxiliaries, I would argue) - the killings of Jews drew upon deeper layers of hatred. Hatred which, like weeds, sprung from the toxic soil of antisemitism which grew deep over time, enriched and cultivated by centuries of the teachings of the Church and decades of secular, nationalistic indoctrination. Greed, opportunism, or fear were therefore powerful, but secondary motivations for the gentile killers of their own Jewish neighbors.

Thank you

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)